Interactive Voice Response has existed since the 1970s. Autonomous cars using neural networks were first developed in the 1980s. When will conversational chatbots deliver? This post discusses old and recent AI developments and makes the case for human-in-the-loop AI for customer conversations from the perspectives of technology development, user experience, and business learnings.

Contents

Motivation/Context

In recent years, automation has been a trending topic. With advances in artificial intelligence, particularly in a subfield of machine learning termed deep learning, AI systems now appear capable of tasks such as autonomous driving, holding conversations, and common back-office tasks.

There have been astounding advances in AI research, with applications in object detection, speech transcription, machine translation, and robotic control. Yet, we see a lack of disciplined reasoning when it comes both to developing and purchasing these systems. Many parallels to the AI wave can be drawn from prior technological breakthroughs. In most of these breakthrough moments, it took a period of time for the technology base to be sufficiently mature for wide adoption. Despite protocols, such as the World Wide Web, that have accelerated the propagation and adoption of technological advances, we at Sapling believe that for tasks such as holding conversations with customers, a human-in-the-loop solution is best when excluding the most transactional of interactions.

This essay argues for human-in-the-loop conversations, starting from first principles. We draw upon analogies in other fields such as autonomous driving and automated call handling. While we first focus on the maturity of the technology, we later discuss the advantages of human-to-human conversations.

Why Now

“There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”

― Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov

Two changes prompted us to write this essay.

- The first is the rise of AI and machine learning, in particular the rapid adoption of AI technology by industry.

- The second, related change is the rise of automation, in particular with chat-based support and inside sales stretching customer-facing teams thin. The COVID-19 virus further accelerates the need for automation for many businesses.

Examples from History

To begin, we provide some historical perspective by describing the adoption of technology for two other developments: interactive voice responses and autonomous vehicles.

Interactive Voice Response

Interactive voice response (IVR) systems are familiar to almost everyone. You call a bank, or your cable provider, or a large health provider, and an automated responder collects some basic information from you and tries to route you to the right information (or just punts and gets you off the line). These systems extend as far back as the 1970s. It was only in the 2000s, however, that improvements in speech recognition and in CPU processing power made IVR more widely deployable.

Unfortunately, IVR never lived up to its promise. While IVR can handle simple decision trees and recognize customer responses from a heavily constrained set of possible responses (“say yes” or “say your account number”), much of the functionality may as well be transformed into a simple webpage form—no AI necessary.

Recent systems allow for the transcription of calls for later inspection—however, these tools are for quickly analyzing calls instead of responding to customers in real-time. Ultimately, a true IVR layers the complexity of speech recognition on top of chatbot technology. Until helpful customer-facing chatbot systems are developed, we see no reason to expect IVR’s capabilities to expand (this includes certain products under development by Fortune 500 companies that you may have heard of in recent years).

Autonomous Vehicles

While it seems autonomous driving has only become a hot topic in the last five years, with Google’s Waymo, Tesla, and upstarts such as Aurora, the history of machine learning for autonomous driving extends far past 2015.

Carnegie Mellon University published results on an autonomous truck in 1989—the year of the fall of the Berlin Wall—and development had started five years prior. Not only did the vehicle use machine learning, but it in fact used neural networks—the machine learning model that later developed into deep learning—in order to predict steering wheel positions from images of the road ahead. All more than 30 years ago.

In 2004, the first DARPA Grand Challenge was held to determine whether a research team could design a vehicle to autonomously drive along a 240-km route in the Mojave Desert. While no vehicle completed the route in 2004, in the second Grand Challenge in 2005 five competitors completed a 212-km off-road course. It seemed autonomous vehicles were near.

Yet 15 years later, tens of billions of dollars invested, and the smartest people in the world working on the problem, autonomous vehicles are still restricted to a small number of riders along specific routes, or fall back on teleoperation. Reasons for this include the much greater difficulty of driving on crowded local roads, the high levels of safety required of such systems, and the many conditions such systems must handle.

Automating Conversations

Given the history of previous technology products that took some time to reach mainstream adoption, we now turn to automated conversational systems and human-in-the-loop conversational aides. We loosely refer to automated conversation systems at chatbots and human-in-the-loop systems as conversational assistants. From our previous discussion on IVR, we consider speech-based assistants—such as Samantha from Her—as a wrapper around a core language-understanding system that relies purely on text. This has inaccuracies as voice can communicate emotions and other cues that pure text cannot, but to simplify the discussion we’ll make this assumption.

FAANG and Existing Systems

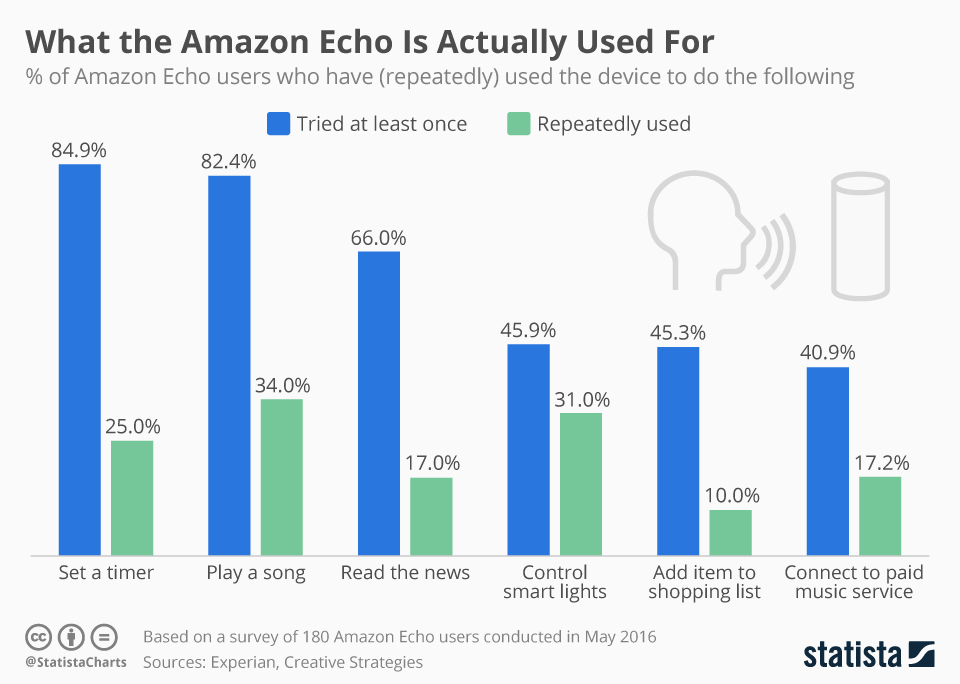

To start, consider the companies that are best positioned to deploy a chatbot system—namely, the FAANG companies. Google, FB, Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon have orders of magnitude more data and orders of magnitude more money (and therefore compute) to train and deploy machine learning systems on that data—and with the establishment of research labs, more AI talent as well.

Besides having the resources, these companies are also incentivized to deploy these systems, as many of their core products are for communication. In the case of Google, Gmail and Meetings, for Facebook, Messenger and Whatsapp, for Microsoft, Outlook and LinkedIn, and for Amazon, of course there’s Alexa—just to sample a few examples.

Considering these companies, however, what are the communication assistants that have been deployed? How many turns of conversation can they handle? What level of depth do the suggested responses handle? And in how many cases are the replies in fact fully automated?

(For more on why this is the case, you can find an explanation here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ihmm_tQGBeE&t=3m15s)

UX Perspective

From a user perspective, is chat actually the best option? It’s easy to say that natural language is an intuitive interface, but in many cases natural language is not efficient at all. Consider the following examples:

- Purchasing a product: Imagine going to a retail website and not being able to search and scroll through products, but instead being forced to go back and forth with a chatbot to narrow down to the product you want.

- Updating an account: It’s much easier to use browser autofill.

- Getting clarifying information: It’d be faster if that information were instead in a FAQ.

The problem with chat (and of voice as well) is that it constrains the interaction to a single thread, while the web is designed to allow for parallel blocks of information to be displayed to the user. For highly transactional, self-service tasks, simple webviews are often the best solution. This then leaves tasks that require more back-and-forth and complex interaction—namely, tasks that require human intervention.

| Simple Task | Complex Task | |

| Faster Resolution | App Webview | Human Chat |

| Slower Resolution | IVR/Chatbots | Human Ticket/Call |

Chitchat vs. Tasks

A minor point: there exist chatbots in broad use that provide chitchat functionality. These chatbots serve to entertain and in some cases inform users without requiring precise understanding of the conversation or the ability to manage information from many turns ago. The discussion above is not about chitchat bots, but instead bots that act as assistants intended to help complete tasks—which entails precise understanding and management of longer-term information.

Business Implications

Assuming a company is looking to automate certain conversational sequences or convert them to self-service, it’s fair to assume that they feel they have a good grasp of all the possible variations of those conversations. Even in these cases, there can be significant drawbacks to full automation beyond the speed vs. quality tradeoff.

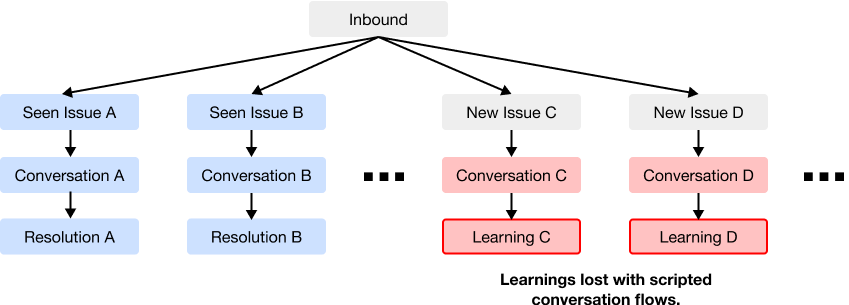

Conversational Insights

Customer conversations are a key source of feedback in order to improve product and other aspects of a business. Guiding customers down fixed paths with decision trees and click-to-accept options prunes away new and diverse feedback from customers—the more open-ended the interaction, the more opportunity there is to learn from the interaction, and this is especially true for the long tail. Automated pathways push users along the beaten paths of past interactions, while conversations should also provide insights from unvisited paths.

Adaptability

With the increased expressive power of deep learning systems and their ability to improve with more data comes a price: deep neural networks are not as interpretable or controllable as traditional methods.

Thus modern deep learning systems will often yield the best results on existing benchmarks, they are not well-suited for rapid adaptation to new requirements. On the other hand, humans shine at rapidly changing their behavior and navigating fuzzy requirements.

| Chatbots | Humans |

| Consistent | Personal |

| Immediate | Delayed |

| Simple scenarios | Simple and complex scenarios |

| Adapt infrequently | Adapt quickly |

Assisting Agents

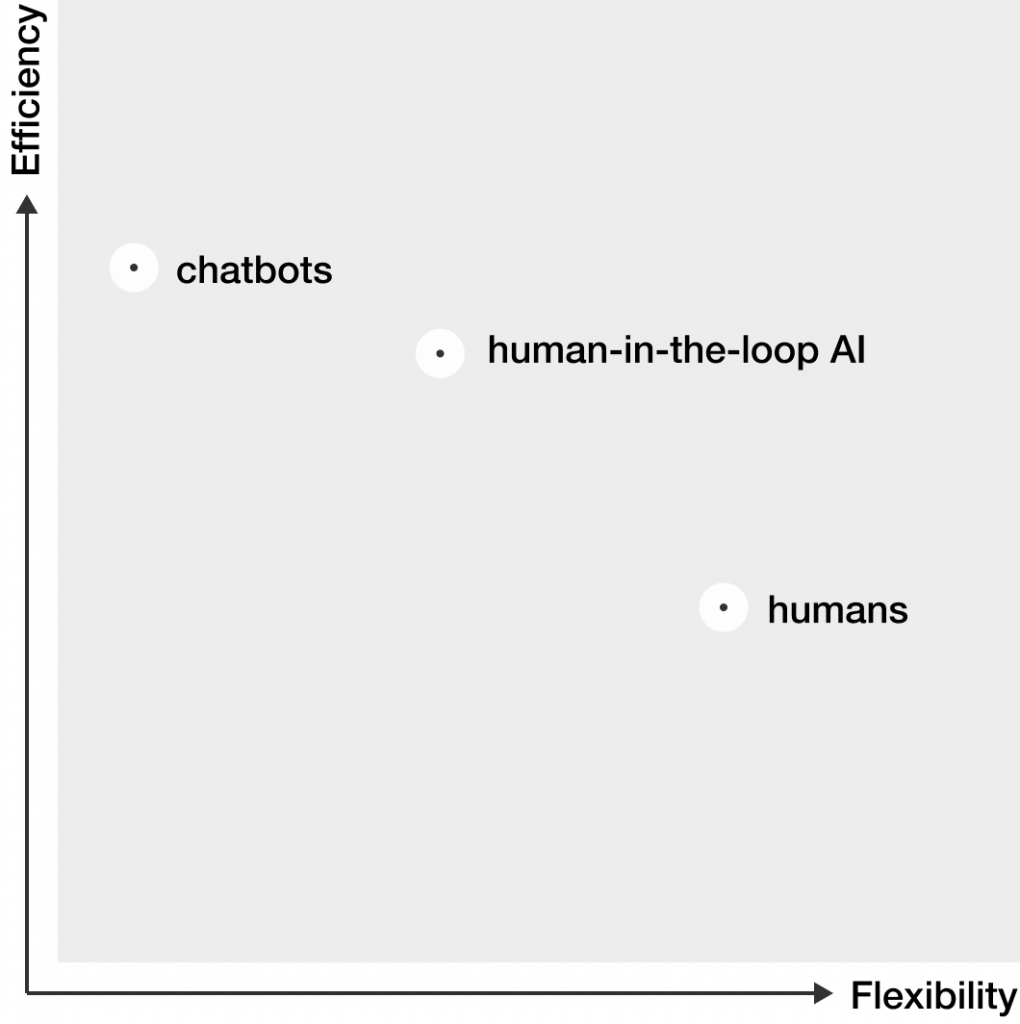

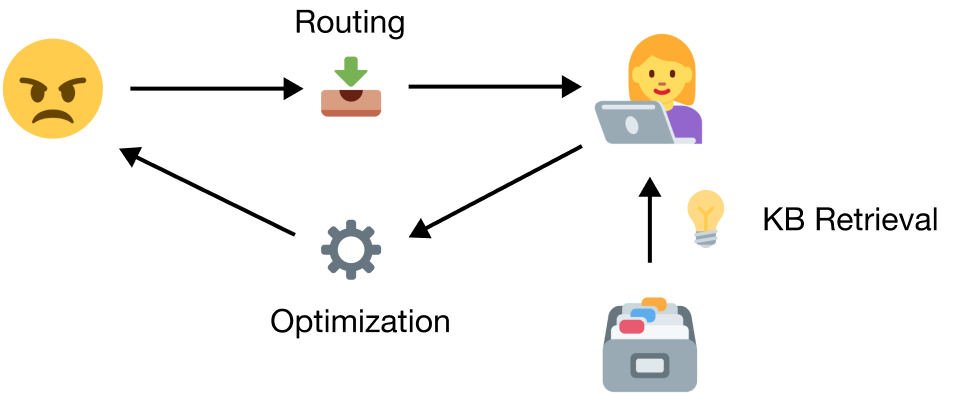

Finally, assuming that a human-in-the-loop is desired, how can AI technology best empower agents while helping the business?

The Business Perspective

We consider two axes along which human-in-the-loop AI can help businesses. The first is by improving the efficiency of teams, and the second by improving the quality.

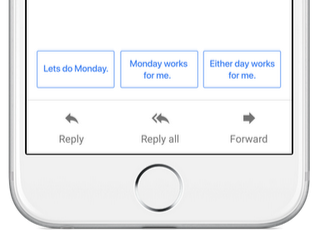

Ways by which AI tools can yield efficiency gains include retrieving information (for the agent as well as the customer), segmenting and routing customer groups to the right resources, and suggesting responses or partial responses to the agent. In contrast to fully automated approaches, these tasks can easily include a human approval step or can be overridden by the customer.

| Task | Example(s) |

| Retrieve information | Fetch knowledge base article that may address customer question. |

| Segmenting/routing | Identify common issues by segmenting tickets into buckets. Route a particular customer request to the right customer service department. |

| Suggesting responses | Chat assist where agents can simply click on the desired response. |

Besides enabling gains in efficiency, AI assistants can improve quality metrics such as CSAT (satisfaction) and CES (customer effort) as well. Searching through the knowledge base ensures that customers receive the information they need. Routing requests to the right department similarly helps improve resolution rates. Agents are faced with typing the same repetitive replies to inbound messages; suggested responses can help streamline their chat workflow. AI can further help sanity check messages for language quality and compliance.

The Agent Perspective

From our own time developing tools for agents, we’ve found a few key requirements for tools that deliver returns on investment:

- The tool must help consistently. If it helps just 5% of the time, it gets used 0% of the time.

- The tool must sit within existing workflows. Whatever helpdesk or sales engagement platform the agents are already using, the tool should be integrated with. It’s too much to ask for an agent to context switch to the tool in order to receive assistance.

- The tool should rely on the agent or customer to make decisions that have any significant uncertainty–—augmenting the capabilities of humans instead of automating them away. This is the argument we’ve been making throughout. ■

About Sapling

At Sapling, we’re building the intelligence layer for chats, tickets, and emails. Our team has over a dozen years of experience in machine learning and deep learning at the Berkeley AI Research Lab, the Stanford AI Lab, and Google’s Brain Team. The Sapling product suite is used by teams supporting startups as well as several Fortune 500 companies.

The Sapling Blog describes our learnings from developing solutions for customer-facing teams using the latest AI technology.

If you want us to email you when we publish new essays, sign up for our newsletter below (we’ll ping you biweekly or monthly, no more than that).